It took eight years to complete, The Butcher of Cairo. Yet it is the shortest of my five published crime novels. For that, I have to thank book critic Marilyn Stasio, and the ghost of Hemingway.

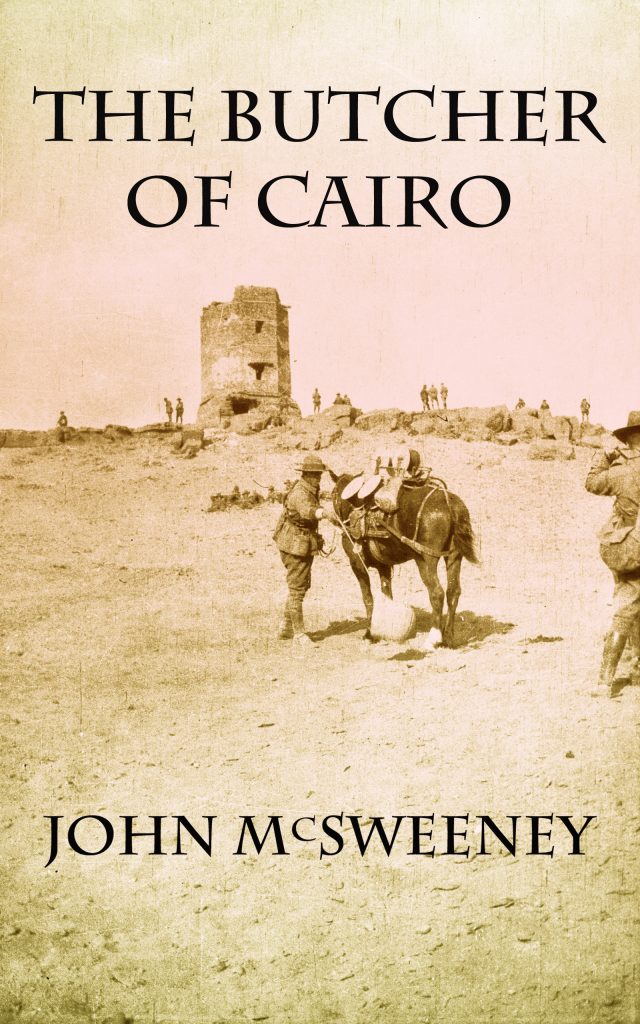

The Butcher of Cairo – A serial killer hides in plain sight as ANZAC troops prepare for war.

The Butcher’s Difficult Birth

The Protagonist Problem

In 2010, I began work on a crime novel set in Egypt during WW1.

I settled on a protagonist, a soldier with a criminal background. He was, in part, based on my grandfather, Frank Cave.

In these early drafts, soldiers dropped like flies under the Egyptian sun as they prepared for war. And that was good. Evil is excellent.

But it didn’t work out, because I asked myself, Will a reader feel any empathy for my protagonist? The answer was no. Definitely not. And if I was keen to do him down, I could only imagine the reader thinking, Get on with it. Kill the bastard!

Also I’m no Patricia Highsmith.

So I settled on another protagonist, Sergeant James Fraser, an Australian military policeman. That offered me the chance to tell the story from another point of view.

Killing Holmes

Then, to make matters more interesting, I gave Fraser an assistant, Christian Winter, an Aboriginal Australian.

As is the way of these things, I made life even more difficult for myself. Because midway through the story, I killed off Fraser.

This was akin to polishing off Holmes and leaving Watson to carry on alone. This was not a good idea. In fact it was downright terrible.

Cultural Misappropriation

I struggled with this approach for a long time. I explored Aboriginal Australian culture. But in the end I called a halt. In part, that was due to a feeling that I was teetering on the edge of cultural exploitation. But I also failed to develop Winter’s character in a satisfying manner. I was unable to develop relationships between him and anyone else. He was too much of a loner. So I stopped work on the book. Then I began writing another one and painting a few pictures.

Crime and Character

In 2017, I dusted down my WW1 whodunit. I changed the title twice. But that was a sticking plaster when it required radical surgery.

I thought I knew how to fix it. There was a crime. Someone dies. Then someone else solves it.

But my characters needed fleshing out. So I spent ages on them. Giving them likes and dislikes, and all the while making sure the word count rose steadily above 60,000. Because a novel is no such thing if it doesn’t join the eleven-mile-high club.

Yet again I was wrong, and so was Fraser. He kept making mistakes.

So the two of us spent another six months putting things right.

Historical Research

As with my other novels, I spent a lot of time researching before and during writing.

I made use of archives kept by the Australian War Museum — it’s where I found my grandfather’s military records.

I delved into diaries. I found evidence of much wickedness, as well as heroism.

But I was in danger of succumbing to information overload. I needed help. I needed Marilyn

Sound Advice – The Stasio Effect

I became an avid listener of podcasts. One in particular was Criminal.

Several months ago, in an episode called The Gatekeeper, Phoebe Judge interviewed Marilyn Stasio.

Ms Stasio reviews crime novels for the New York Times Book Review.

During the interview, she said, “No one writes puzzles any more.”

And she is apt to ask, when reading, “Where’s the body? Kill someone! Let’s get out of here! Let’s move this along.”

“Violence is fine,” she said. “It’s why we read it. It’s exciting.”

She also said, “In the past the emphasis was on the crime, the victim, the procedure of how the detective went about solving the crime. Today it is about character and the insertion of the author, an identification with the lead character. You learn everything about this character that you don’t give a shit about.”

“The detail gives pleasure to the author, not the reader.”

She also hates the work of Philip Roth.

I thought, she’s my kind of girl.

The Puzzle

The puzzle I created took me eight years to produce.

I did try and simplify it. But The Gatekeeper convinced me not to.

So a warning. It’s a headbanger. Though it does hold together.

And of course history lent a hand … But I don’t want to give too much away.

Enter Hemingway

Marilyn Stasio also convinced me to cut, cut, and cut.

So I butchered adverbs and machine-gunned the superfluous. I took an axe to the passive voice. In short, I went all Hemingway on it.

Finally …

I don’t know if Marilyn Stasio would give my novel the time of day. Maybe there is still too much of the characters getting in the way of the body count. But I do think she helped me finish my novel.

So thank you, Marylin, you’re a sweetie, albeit a hard-boiled one.

Selected Reading

The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, C.E.W. Bean, Australia: Angus & Robertson Ltd

Volume 1 The Story of ANZAC: From the Outbreak of War to the End of the First Phase of the Gallipoli Campaign, May 4, 1915

Volume 2 The Story of ANZAC: from 4 May, 1915 to the Evacuation

The Australian Army Medical Services in the War of 1914-1918, Volume I, PART I, The Gallipoli Campaign by Colonel A. C. BUTLER, Australian War Memorial, Melbourne, 1938

Australian Imperial Force War Diaries

Australian Units – 15th Battalion: February 1915, March 1915, April 1915, May 1915, June 1915

New Zealand Units – Auckland Battalion: May 1915, June 1915, July 1915

Quinn’s Post, Peter Stanley, Allen and Unwin.

Accommodating the King’s Hard Bargain: Military Detention in the Australian Army 1914 – 1947, Graham Wilson, Big Sky Publishing.

The Other Enemy, Australian Soldiers and the Military Police, Glenn Wahlert, Oxford University Press

Hashish: A Smuggler’s Tale, Henry de Monfried, Penguin Books

Egyptian Service 1902-1946, Sir Thomas Russell Pasha, London John Murray

Bowler of Gallipoli : witness to the Anzac legend, Frank Glen, Australian Military History Publications