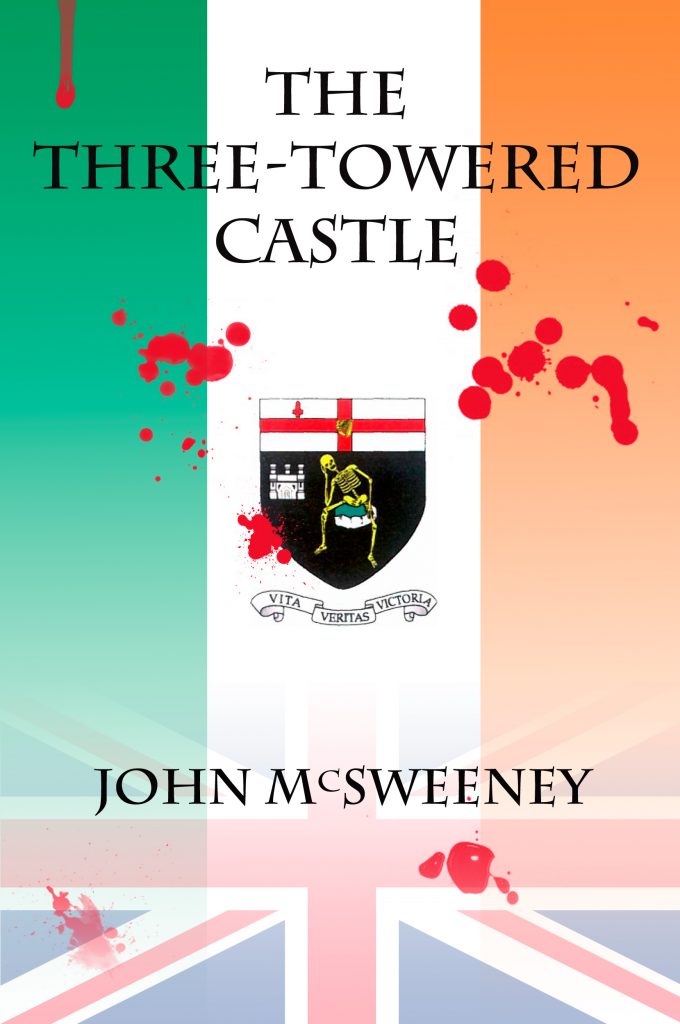

My novel The Three-Towered Castle is set in Ireland during 1970. It took me seven years to complete, and at one stage I employed an editor who said readers were unlikely to have a clue about Irish affairs, and so she suggested I write an introductory essay. As a result this essay, A Short History of Ireland, acts as a foreword to that book.

The Three-Towered Castle, a tale of a B Man, a boy and a bloody history

You can read about its genesis here.

My novel is set in 1970, and it takes place either side of an Irish border that pays little heed to geography. Indeed, as the reader will discover, not only does the border divide north from south and east from west, it also cuts through properties, thus enabling a farmer to get out of bed in the Republic, take a short walk across his land and, without leaving it, arrive in the United Kingdom.

Any explanation as to how this came about is bound to be contentious. Nonetheless I will chance my arm and elect to begin with Dermot MacMurrough, the King of Leinster, who lost his kingdom after abducting the wife of another Irish king. In order to win it back, MacMurrough requested the help of Norman knights who in 1169 landed near Bannow in the southeast of Ireland.

Having restored MacMurrough to his throne, the Normans, under the aegis of Henry II, sized up the lie of the land, decided it was worth staying and quickly outwore their welcome, as did a succession of English monarchs who were intent on strengthening their grip on Ireland.

In the 16th Century, Henry VIII’s Reformation of Catholicism in Ireland was met with resistance, whereupon the English responded by pursuing a policy of colonization.

The Plantation of Ulster, which began in 1609, forced Catholics from their land, replacing them with Protestants from England and Scotland. Elsewhere, Penal Laws punished both Catholics and Presbyterian dissenters. As a result, Catholics, by far the majority, were prohibited from inheriting land and banished from the Irish Parliament in Dublin.

Rebellion followed in 1641, during which time thousands of Protestant planters in the north were massacred.

An English civil war delayed large scale retaliation until 1649 when Oliver Cromwell became as popular as the bubonic plague that had ravaged the country. Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland was relentlessly brutal, punishment for the Ulster massacres, and fuelled by sectarian hatred.

In 1688, revolution in England had consequences for Ireland when Catholic Jacobites in support of King James II fought against William of Orange’s Protestant troops. The Siege of Derry in 1689, when Protestant defenders starved to death before the city was relieved by the Royal Navy, was followed by the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, after which James fled to France. These were to prove seminal events in Protestant lore.

The rise of the Protestant Ascendancy, whereby the minority exerted control over Ireland, and resistance to it by the majority, thus created the template for what was to follow.

In 1798, members of the Society of United Irishmen, supported by a revolutionary French government, rebelled against Britain. They were intent on promoting both Catholic and Presbyterian rights by replacing Crown rule with an independent republic, much the same as that achieved in America. However the rebellion was crushed and its Protestant leader, Wolfe Tone, died by his own hand rather than face execution.

Following this, in 1800, the Acts of Union created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. This led to the dissolution of the Irish Parliament. Proponents viewed it as a means of fending off French interests while partially addressing Protestant supremacy. However Catholics thought otherwise, either embarking on a struggle for emancipation in the form of a fully independent republic, or pursuing a measure of autonomy without severing ties to the British monarchy, so-called Home Rule.

The Irish Question, as articulated by Disraeli, required a solution to “a starving population, an absentee aristocracy, and an alien Church; and in addition the weakest executive in the world.”

In 1912, following previous failed attempts, the British Government introduced the Third Home Rule Bill which would re-establish a Dublin Parliament. This was fiercely contested by Unionists led by Sir Edward Carson who saw nothing other than a slippery slope to a republic. Consequently a large militia — the Ulster Volunteer Force — was raised and armed by Germany.

The following year, in the south, nationalists and republicans responded by forming their own militia, the Irish Volunteers. Thus Britain and Ireland, the United Kingdom, faced the prospect of a civil war.

The Third Home Rule Act was passed in May 1914. However within weeks, the British Government postponed its implementation following the outbreak of the First World War. Moreover threats of Unionist insurrection subsided when Carson offered his troops in service of the King. Carson’s business was put on hold, to be continued once the war, which was expected to be short, was over. The UVF subsequently became the 36th Ulster Division, eventually suffering appalling casualties at the Battle of the Somme.

Britain’s call to arms caused a split within the Irish Volunteers, with most choosing to be absorbed into regular Irish regiments — ironically fighting alongside the Ulster Division — while the rest found themselves under the control of an Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) determined to overthrow British rule.

In 1916, members of the IRB organized an uprising in Dublin, resulting in the declaration of an Irish Republic. The Easter Uprising was quickly put down by both British and Irish forces, and the rebellion’s leaders were executed.

In 1918, with anti-British resentment increasing in the wake of these executions, a General Election saw the republican party of Sinn Féin win the majority of seats in the south of Ireland. Sinn Féin subsequently refused to sit in Westminster’s Parliament, choosing instead to form a revolutionary Irish Parliament in Dublin — Dáil Éireann. As a consequence, in 1919, war broke out between the Irish Republican Army, many of whom were Irish Volunteers supporting this First Dáil, and those forces acting on behalf of the British Government.

In late 1920, with the Anglo-Irish war still raging, the UK Parliament attempted to solve what was now being described as the Irish Problem by passing the Government of Ireland Act. This would divide the 32 counties of Ireland into two parts. Northern Ireland, with its Protestant majority, would now consist of 6 counties of Ulster* to be governed by a Parliament in Belfast. The other 26 predominantly Catholic counties would form Southern Ireland, governed by a Parliament in Dublin. However defence, foreign policy, matters of currency and international trade were to remain the responsibility of Westminster.

In May 1921, with British and Irish forces deadlocked, elections were mounted throughout Ireland. However in the south no polling took place and 124 members of Sinn Féin and 4 independent Unionists were returned unopposed, thus forming the Second Dáil, albeit with a refusal by the Unionists to recognise it.

In the north, the Ulster Unionist Party won 40 of the seats in Stormont, the home of Belfast’s Parliament. Sinn Féin won 6, while the remaining 6 were taken by the Nationalist Party. Thus Ireland remained divided by two polarised forces of unionism and nationalism, although it is worth noting those wishing to maintain the Union were not, and are still not, exclusively Protestant, in the same way nationalists have never been exclusively Catholic.

Shortly after the elections, the Anglo-Irish War ended when a ceasefire was declared. An Anglo-Irish Treaty was negotiated by the British Government and the Second Dáil. This resulted in all 32 Irish counties forming the Irish Free State — a dominion in the mould of Canada and Australia. However, and most crucially, Northern Ireland would be given the choice of maintaining self governance, which unsurprisingly, given its Unionist majority, it did, electing to immediately withdraw from the Irish Free State.

Provision was also made within the Treaty for an Irish Boundary Commission to precisely define the border. This it did in 1922, albeit provisionally and without any input from either Sinn Féin or the Northern government who both refused to participate. The net result was Irish nationalists felt robbed of land, while Unionists took the view that the 6 counties represented a viable province which they could successfully defend.

The Treaty divided republicans, with some regarding it as a betrayal of the Easter Rising and First Dáil. This set in motion a civil war lasting almost a year, ending in May 1923 when pro-Treaty Irish Free State forces, with support from the British Army, defeated the IRA. However pro-Treaty did not mean pro-North, and the Irish Government continued to lay claim to the 6 counties, much to the consternation of the northern Unionist majority.

During the ensuing years, Ireland remained constitutionally linked to the UK via the monarchy until in 1948 the Republic of Ireland achieved full autonomy.

Since the central character in my novel is a member of the Ulster Special Constabulary mention should be made of their contribution. The USC was formed in 1920. Its members, best known as the B Specials, formed an almost entirely Protestant militia which acted as a reserve for the Royal Ulster Constabulary.

Informed opinion, either side of the border, believes that without the Bs Northern Ireland would have fallen to the republican forces of Sinn Féin and the Irish Republican Army. For this reason they were lionised by Protestant loyalists, but they were also hated, feared and resented by a broad spectrum of the northern Catholic minority.

Now to two figures who also make fleeting appearances in my story.

Reverend Ian Paisley was the Moderator of the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster. He founded it in 1951 while still in his twenties, at a time when he was also a member of the Protestant fraternal Orange Order. He had hoped to use Orange halls for his meetings, however the Order passed a resolution preventing Free Presbyterians from doing so, whereupon an incensed Paisley accused them of ecumenism, which in his book was tantamount to treason, no spoon being long enough to sup with Catholics.

Paisley spent decades contesting, agitating and forcing those in power to do his bidding, spending two spells in prison for his beliefs. However one episode will suffice to show how he went about his work.

In the run up to the 1964 General Election — for seats in Westminster’s Parliament rather than Northern Ireland’s — Paisley took offence after discovering an Irish tricolour had been hung in the window of Sinn Féin’s Belfast office. Paisley demanded its removal, citing Northern Ireland’s highly contentious Flags and Emblems Act which made it illegal to display any flag other than one representing the Union.

Although the Royal Ulster Constabulary usually turned a blind eye to such matters, Paisley threatened to march with his supporters to the scene of the crime and remove the flag, and so the RUC arrived in armoured cars and seized it.

Sinn Féin soon replaced the tricolour, whereupon the RUC paid a second visit. This time the police were met by a storm of rocks, iron gratings and petrol bombs, all delivered by outraged republicans.

Meanwhile, Paisley led prayer meetings, leaving Northern Ireland’s Prime Minister, Captain Terence O’Neill, to call for restraint. Paisley in turn accused O’Neill of weakness in the face of republicanism. It was a tactic Paisley continued to use during his rise to the pinnacle of Northern Irish politics.

Now to Bernadette Devlin. Catholic born, she came to prominence in 1968 as a founder of People’s Democracy, a Socialist-Marxist grouping of civil rights campaigners formed at Queen’s University Belfast.

On April 17, 1969, and still only 21 years of age, Devlin won the Mid Ulster by-election for a seat in Westminster’s Parliament. At the time, she was the youngest person ever to do so. She began her career, much as she would continue, by contesting what she saw as widespread injustice against the minority in the North.

On August 12, 1969, Northern Ireland reached a tipping point when the Apprentice Boys of Derry marched, as they did every year, in memory of the Siege of 1689. This took them through the city and close to the Catholic enclave of the Bogside. Its inhabitants, along with neighbours from the Creggan, were outraged at what they perceived as yet another demonstration of Protestant Unionist supremacy. Insults were freely exchanged and rocks were thrown by those in the Bogside as well as loyalist supporters of the marchers.

The RUC attempted to drive the Catholic-nationalist faction back with sticks, eventually resorting to the use of CS gas. Meanwhile, the B Specials were placed on standby while the Bogsiders used petrol bombs to expel the RUC. Among those fighting the police, inspiring, leading, inciting — one takes one’s pick according to one’s colours — was Bernadette Devlin, and for this she would eventually be sentenced to prison.

At the instigation of Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, the fighting in Derry spread across the country in an attempt to stretch the RUC to breaking point. As a result, Belfast burned and the sectarian divide was blown apart by bombs and guns.

After three days of pitched battles, with the RUC exhausted to the point of collapse, the British Army arrived and wedged itself between the warring factions. The soldiers immediately set about placing barbwire and barriers on the streets of Belfast, thus forming a supposed peace-line.

In the meantime, the Bogside and the Creggan were declared a no-go area. Free Derry was established and controlled by local activists, including Derry’s Officer Commanding of the IRA.

Soon afterwards, in Belfast, loyalists shot and killed a RUC officer, and British soldiers shot dead two Protestants. The British Government responded by placing Northern Ireland’s security firmly in the hands of the Army.

As for the B Specials, Westminster demanded they hand in their guns with a view to eventual disbandment. This decision was met by Protestant outrage with Paisley accusing Westminster of removing Northern Ireland’s last line of defence against Dublin, saying civil rights protests were simply “a smokescreen for the republican movement”.

Still, the IRA was not exempt from criticism, not even from its own. When Belfast’s Catholics and republicans asked after the whereabouts of their defenders, many believed the answer lay further south in Dublin, where men steeped in Marxist politics were seemingly oblivious to the plight of those in the north. In turn, the Dubliners harboured suspicions of northerners who had failed to lend their support a decade earlier during the ill-fated Border Campaign, and so the guns remained cached south of the border. To add insult to republican injury, I Ran Away passed into everyday language as both Belfast and Derry continued to simmer.

In October 1969, the British Government’s Home Secretary, James Callaghan, visited Northern Ireland. In Derry he was welcomed by Catholics, and Bogside activists soon gave way to the Royal Military Police who together with troops were greeted with cups of tea, sandwiches and handshakes. But in Protestant areas, on both sides of the River Foyle, feelings were very different, and Sunny Jim Callaghan was forced to confront a frosty and at times a hostile response when Loyalists accused him of not only selling them out, but also labelling him a Fenian lover.

At the end of 1969, a split in republican ranks broke out into the open with the creation of two groups. The Official IRA, the Stickies — thus named because of the adhesive on their Easter lily badges — maintained a non-sectarian struggle against capitalism, whereas the Provisional IRA — the Provos — believed in the more traditional form of physical force republicanism.

As winter bit there were those who feared losing their stranglehold on power. Unionists in Stormont found themselves caught between preserving the status quo and being forced by Westminster to grant civil rights to Catholics, while a number of Protestant loyalists in Belfast looked to arms and explosives as the best means of fighting the IRA.

The British Army struggled to maintain any semblance of peace, and soldiers were fast becoming the meat in a most unhealthy sandwich. Certain elements within the military regarded the situation as akin to the insurgencies seen in the likes of Malaya, Kenya and Aden, adopting less than orthodox tactics in order to defeat the IRA, even if it meant colluding with Protestant loyalists who were none too fussed about the legality of their actions.

Consequently, by early 1970, some six months after the opening scenes had been performed, the stage was set for the rest of the tragedy, one which eventually took the lives of more than 3500 people while injuring and maiming more than thirty times that number during a period of 32 years.

* The province of Ulster consisted, and still does, of 9 counties. After division, Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone were assigned to the North, while Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan were to be governed from Dublin.

Selected reading

- The I.R.A. — Tim Pat Coogan (Harper Collins)

- THE ‘B’ SPECIALS, A history of The Ulster Special Constabulary — Sir Arthur Hezlet (Pan Books)

- VOICES FROM THE GRAVE, Two Men’s War in Ireland — Ed Maloney (Faber and Faber)

- A Secret History of the IRA — Ed Maloney (Penguin Books)

- THE ORANGE ORDER, A Contemporary Northern Irish History — Eric P. Kaufmann (Oxford University Press)

- The IRA and Armed Struggle — Rogelio Alonso (Taylor & Francis)

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers’ Party — Brian Hanley and Scott Miller (Penguin Books)

- EASTER 1916, The Irish Rebellion — Charles Townshend (Penguin Books)

- Violence and nationalist politics in Derry City, 1920-1923 — Ronan Gallagher (Four Courts Press)

- The Bloody Sunday Inquiry — The Rt Hon Lord Saville of Newdigate (Chairman) — (The National Archives: www.bloody-sunday-inquiry.org.uk/)