My father, Albert McSweeney — better known as Mack — worked as a porter in Covent Garden Market for most of his adult life.

Covent Garden Market, circa 1963

In this photograph, my father is pulling a barrow and looking to his left. This was probably as a precaution against traffic, but it is equally possible that he was on the lookout for Old Bill in the unlikely event police were doing their job and collaring villains.

My father often described his working day as one spent ducking and diving.

To do him justice, an ironic term given his uncanny ability to avoid the clutches of the law, requires something considerably more than a passing mention, and so my essay about his life attempts to paint a fuller picture.

Alfred Hitchcock made use of the market’s light-fingered activities to great effect for one scene in his film Frenzy. You can read more about this here.

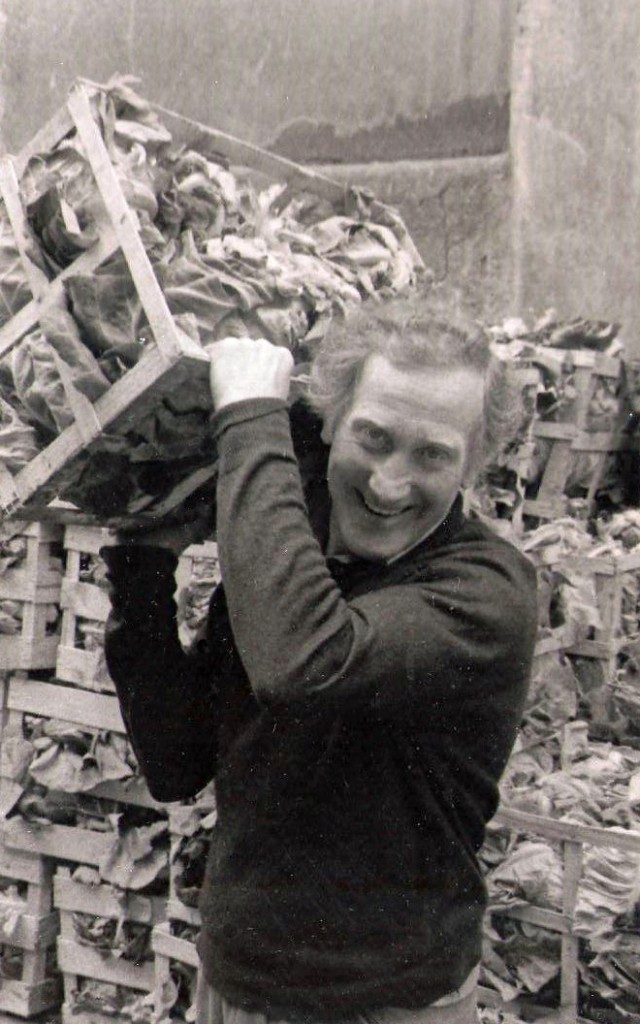

My father, Albert McSweeney, Covent Garden Market, circa 1973

When I was young, my mother would occasionally take me to see him at work. He would place me on his barrow, along with hessian sacks of vegetables and wooden crates of fruit. Then he would pull me up and along Bow Street, or across the cobbled stones of the Hall Yard, which is now buried beneath the Royal Opera House Souvenir Shop.

As Green as Lettuce

In the summer of 1971, I worked in the market as a porter. I was a university student at the time, and as green as an English lettuce.

Howard Chapman* was foolish enough to employ me. The firm was situated on 107, Long Acre on a site now occupied by Russell & Bromley shoe shop.

*The Vestey family owned Howard Chapman. They also owned the Dewhurst butchery business.

Work began at 6 a.m., whereupon the foreman would take his breakfast in the Essex Serpent aka The Snakepit. As a result, he was drunk when he returned at 7.

The Snakepit was sited on 6 King Street. Like Howard Chapman, it is now a shoe shop.

The market was in constant motion all morning. But by mid afternoon it resembled a ghost town, only to spring back to life in the early evening when theatre and opera goers would descend on the area.

My father also worked as stagehand in a number of theatres, as did many porters. I did too.

During Spring and Summer the market would operate on Saturday mornings. Sunday of course was a day of rest, and one certainly needed it, unless of course one turned out for a local football club. What happened to that boundless energy? I knew several porters who had successful careers as amateur footballers.

Harry Hutchins, (see below) was a very talented player, as was my father who turned down terms with QPR following the end of WW2, during which time he played for the Royal Navy. His reasons? Being a professional footballer in those days did not pay enough. Even more shocking is my grandfather’s rejection of professional terms with Chelsea when he left the army at the end of WW1, for the very same reasons.

Harry Hutchins (left) and Albert McSweeney. Covent Garden circa 1950

My working life as a porter was short and not exactly covered in glory. My party trick was to upend loaded trolleys of fruit along the length and breadth of the market. How I hated that sharp downhill left turn leading from Floral Street onto Garrick Street.

Work by Another Name

Meanwhile, miscreants went about their daily business.

One of these gentlemen employed a number of disguises.

When confronting an Italian or a Spanish truck driver, he would don a black beret and a striped T-shirt. Then, in a most appalling cod-French accent, he would invite the driver to adjourn to a nearby greasy spoon for café au lait. Not that Frank’s Cafe ran to anything more than Nescafé.

Meanwhile the rest of the gang set about emptying the dupe’s truck.

If the driver was French, then a suitably dressed Italian would be there to help. The extraordinary thing was that so many drivers fell for it.

I have used this tale of ingenuity in my book A History of Murder.