Kleptomania

My father suffered from kleptomania, which of course means others were affected by his actions.

Despite his light-fingered tendencies, I loved him, and I still miss him. I guess, like most of us, he was many things to many people. In several ways, he was a quite extraordinary man.

This account of his life is drawn from personal memories, his recollections, family lore, and historical research. It represents my attempt to explain the impulses which drove him to steal. I also believe criminal activity is often a manifestation of an underlying psychological disorder, one that is too easily dismissed by those who believe in penal retribution.

“Kleptomania or klopemania is the inability to refrain from the urge for stealing items and is usually done for reasons other than personal use or financial gain.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kleptomania)

A diagnosis

As a child, he was diagnosed with Sydenham’s chorea, historically known as St. Vitus’s dance. It manifests itself as an uncontrollable jerking movement of the body, mostly affecting head, hands and feet. This was most likely a result of contracting rheumatic fever. Family lore has it that when drinking from a glass my father was prone to bite down and shatter it. More tragically, he once dropped his baby sister and as a result she died.

Sydenham’s chorea may lead to obsessive compulsive disorders. Furthermore, kleptomania could be an obsessive compulsive spectrum disorder.

My father had his own rationale for his behaviour, which at no time encompassed a medical condition. He stated on more than one occasion that he stole to provide food and shelter for his family, which is true. He also claimed that he only took from those who could afford it, an assertion which is more debatable. Furthermore, in a fairer world, he believed that wealthy victims of theft should by all rights have shared their wealth with the less fortunate, especially him.

So he believed it was redistribution rather than any felony that he was party to, and surely, he claimed, any reasonable man could see the sense in that.

At this juncture, I think it pertinent to supply some background detail relating to my father’s family and their role in his development.

A Family Affair

My father as a child, circa 1923

My father was born in Camden Town, London, in 1922. His father, also a Londoner, had survived four years of war serving with the Machine Gun Corps.

My grandfather in the uniform of the Machine Gun Corps

My grandmother, another Londoner, was one of eight children.

My father (left) with is mother, Camden Town circa 1928

My grandmother was born to a man who looms large in this tale. I will call him JD.

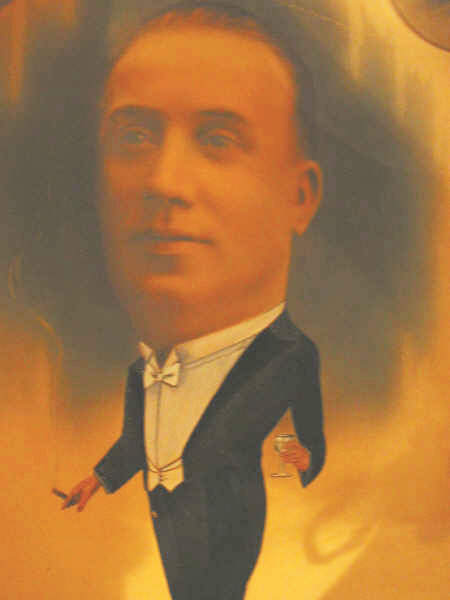

A caricature of my great-grandfather DD

Another member of this large family also plays a significant part in this account. I will call him DD, he was the son of JD and brother to my grandmother.

JD was a very successful bookmaker between the wars. He had a pitch on a well known South Coast racecourse.

In those days, there were no bookmaking shops, and all off course betting was illegal. However JD did not allow this trivial matter to get in the way of business, and like many bookies he took bets whenever and wherever he could. But for that he needed the services of runners.

My father is in the boat, second from left. His mother is in the foreground, far left

My father, like his father, was an excellent athlete. He was fast on his feet and he was very strong. As a teenager, and as a member of St Pancras Boxing Club, and later in the Royal Navy, he had almost two hundred amateur fights. He met and sparred with professional boxers — courtesy of JD.

From an early age he ran the streets of Camden Town in the service of his grandfather. He took bets for JD

When police raided JD’s premises, my father, along with other street urchins, would often hold the door while JD, with his takings, made his exit through a rear window.

The police rewarded the boys with a time-honoured clip around the ear. Later, JD compensated the boys with money.

Meanwhile, my grandfather, who among his other talents was a dab hand with figures, sometimes worked for JD as a tic-tac man, but mostly he was employed as a porter in Covent Garden Market, and unlike his father-in-law he was regarded as an honest and hard working man.

How Not to Treat Kleptomania

JD was fully aware that my father had a problem. So much so that following family visits to JD’s large and well appointed family home, someone would grab my father before he left the scene of the crime and inspect him for stolen goods by turning him upside-down and shaking him.

However JD was nothing if not cognisant of something in my father’s makeup, a trait that closely resembled his own, and he put that to good use.

One could argue that it was mutually beneficial relationship, but I believe there was a degree of coercion. My father was not afraid of anyone that I ever met. However his grandfather was an exception.

On a racecourse, JD carried a sword stick to fend off would-be assailants. My father likened him to Fagin, one who supported an extended family through difficult times.

JD spent his early adult life robbing and stealing. In the early part of the 20th Century he frequented Covent Garden, where horse-drawn cabs deposited opera goers on Great Queen Street, close to where the current Freemason’s Hall now stands. A masked JD, would greet these people and quickly separate them from their valuables.

My great-grandfather enjoyed the company of celebrities, including leading boxers, jockeys and music hall stars, and his great drinking buddy was the Hollywood film actor and Oscar winner, Victor McLaglen.

The Golden Dustman

JD also operated a removal business.

His modus operandi was to arrive at offices in the city with instructions to remove furniture. He also swore that replacements would be arriving later that day, which of course was untrue. Then JD would load the swag onto a horse-drawn cart and take it away.

He was once referred to in print, by a leading Scotland Yard detective, as The Golden Dustman, a reference to Mr Boffin, yet another Dickensian character, this time from Our Mutual Friend.

This detective had good cause to know JD after arresting him for a string of offences. Scotland Yard’s finest thereupon employed the time honoured use of Buggins’ turn. He knew full well that JD had been at it. JD was due a long stretch. Because that was only fair. Moreover, although there was no proof of JD’s crimes, that was not an impediment to a man’s incarceration.

Until this point in time, JD had only once faced court proceedings. In 1920, a judge fined him £50 for running a gaming house in Blackfriars, London.

However JD now faced the certain prospect of a hefty prison sentence. So he offered a the detective a solution which would benefit both parties.

He promised to pay the detective £500, a non trivial sum in those days, and what is more he would find an accomplice who would take the rap by standing in a dock and pleading Guilty.

JD* subsequently found a willing party, an unemployed man**. JD paid him £500. In return, the man spent five years detained at His Majesty’s Pleasure. JD also promised to support the man’s family.

*Ironically, JD came from a long line of police officers, stretching back to the Bow Street Runners.

**In 1968, my father introduced me to this man who was selling evening papers outside Charing Cross Station.

Following this affair, JD went along his sweet way. Then, during 1940, he fell fast asleep on a deckchair, and he did not wake up.

The Fortunes of War

With Hitler making life difficult for everyone, JD’s son, DD, had a problem that he too needed to resolve, only bribery was not an option. A war had suddenly got in the way of making money, and he found himself trapped in the British Army. With his father dead, DD needed to extract himself from this increasingly unhealthy predicament.

DD with my great-grandmother

DD could have declared himself a homosexual. However, as he was a world class womanizer, he searched for another ruse.

The solution was no doubt a little embarrassing; bed-wetting for a grown man never is.

DD set about his unpleasant task every night for four consecutive weeks. That was the benchmark for an Army discharge. Then he returned to civilian life. and set to work.

In May 1940, my father joined an armada of small vessels which set sail for Dunkirk in France,. Once there, he saved drowning soldiers, while also repelling others rather than run the risk of capsizing the boat. Still in his teens, he consigned men, often not much older than himself, to a watery grave.

Shortly after this, he turned eighteen, and he enlisted in the Royal Navy.

Like so many from that era, he displayed great fortitude and no small amount of bravery. In 1942, he took part in the raid on Dieppe, ferrying French Canadians to their deaths. At other times, he served on destroyers, helping to guard convoys of merchant ships bound for Russia. He also took part in the D-Day landings.

My father, HMS Ganges, 1940

Those afflicted with kleptomania pay little heed of war and international boundaries. My father and DD hatched a plan that was to make them a small fortune.

Convoys shipped cargo from the West Indies. There were spices and rum along with food, blankets and equipment from America. My father saw it as a heaven sent opportunity. And so did his uncle.

Able Seaman McSweeney ably organised the theft of these goods from both merchant and Royal Navy ships. When DD welcomed his nephew home, the goods found their inexorable way onto the black market.

The Rum Scam

My father devised a way of rationing rum for American servicemen.

In the spirit of the times, he sold rum to GIs at the extravagant price of £5 a bottle.

But of course there was a catch.

Prior to sales, he drilled a small hole in the bottom of each bottle. Then he drained the rum into a container. Next, he poured cold black tea into the bottles before sealing them. The final touch involved him wiping the necks of the bottles with a rum-soaked rag.

Rinse and repeat, and one can amass a considerable sum.

Copenhagen Killings

Occasionally Dad put his talents to other purposes.

In the final days of the war he found himself in Copenhagen where he met members of the resistance. These men and women were desperate to acquire transport to ferry themselves across the harbour in search of traitors. Dad obliged by stealing a launch, one that he had piloted earlier in the day. He had ferried a senior naval commander across the harbour to accept the German surrender on board the battle cruiser Prinz Eugen.

What followed was three days of drunken blood-letting as the Danes took revenge on those who had collaborated with the enemy.

Once their work was finished, Able Seaman McSweeney returned the launch to the Royal Navy, whereupon the Senior Service rewarded his valour by putting him on a charge.

Crime and Punishment

Dad only served one period of incarceration in his life. That was during the war. It was not for the Copenhagen incident. It happened earlier in the war while eating a meal. Dad complained about the quality of the food. A Petty Officer ordered him to shut up and eat it, whereupon Dad threw the food over the Petty Officer.

That act earned him a month in Chatham Naval Prison. The regime was brutal and while he was there a prisoner was beaten to death by guards. I have checked this account in news archives and it is true. The prison guards were found guilty of manslaughter and received lengthy sentences.

His other brush with Royal Navy authorities occurred in the aftermath of the D-Day landings.

Having landed British soldiers at Ouistreham, code-named Sword, Dad’s landing craft was tasked with repatriating both the wounded and prisoners of war.

One of the latter was an SS colonel, and my father was given the job of minding him.

It was common knowledge that the SS had executed British soldiers during the evacuation from Dunkirk. Thus my father saw the opportunity to perpetrate some rough justice of his own, taking the SS man into a cabin and punching him on the jaw.

It proved to be a lucky blow, or so my father thought. Because a large diamond was ejected from the Nazi’s mouth. Naturally, Dad pocketed the gem.

Unfortunately he had not factored in the possibility that his prisoner would lodge a complaint.

My father was outraged when he was forced to return the diamond to the colonel. And to add injury to insult, Dad was also put on a charge.

A Squandered Fortune

When the war was finally over, he and DD had amassed a considerable sum of money together with a store of goods. They subsequently employed the services of a goods train and ferried the cargo to London.

What happened to this hoard is unknown, at least by me. However my father developed a serious gambling habit, and he subsequently squandered his wealth.

Was this another sign of kleptomania, a compulsive need to splash his ill-gotten gains on horses and greyhounds?

When I learned of his gambling habit, I realised why he had drummed into me from an early age that gambling was a guaranteed way to lose money, claiming that all it did was line the pockets of men like his grandfather.

Yet with JD long dead and DD living a life of moderate comfort on the South Coast*, my father attempted to make a fresh start in London. He took a job in Covent Garden Market, eventually securing a job as a porter alongside his father.

A large tax bill meant that he was desperate to find other ways of supplementing his income. So he took an extra job working nights as a stagehand at the Prince of Wales Theatre.

*DD propped up bars in his later life. People described him as a character, that all encompassing term for a rogue who had seen better days. He died in 1975.

Outback and Payback

In 1965, my parents decided to emigrate to Australia.

My mother’s reasons for doing are described here.

Dad was keen on the move, believing Australia would provide better opportunities for him and his family. An immigration officer in Australia House offered my father the chance to achieve this. Moreover our family were an attractive proposition to the Australian Government. In short, we met the requirements of the White Australia policy.

My father had little in the way of education. He was an unskilled labourer. Yet this immigration officer swore there were ample opportunities to find and secure work.

Unfortunately, on arrival in Adelaide, he quickly discovered this was a bare-faced lie. Once he had experienced a life of unemployment, he became very disillusioned. Australia, he believed, was a godforsaken outback, and as a result he plotted revenge.

He eventually found a decent job, and when he did he took his chance in the manner born.

Victoria Square, Adelaide, November 1967

Sorted

He found work as a sorter in Adelaide’s central mail office.

As the days passed, he gathered names and addresses. He committed them to memory. Then, shortly after he had purchased tickets to return to England, he went shopping.

In those days one could walk into a department store and gain instant credit without any identification.

One simply pointed to a TV or a radio, and said, “I’ll have that. And that. And one of those please. Actually make that two. And I’d like them on credit.”

“Certainly, sir. Would you like these delivered?”

“No. I’ve got my own transport.”

“Very well, sir. Can I have your name and address?”

“Sure.”

And that was it. Goods gone. Buyer gone.

My father did a considerable amount of shopping before we boarded a ship leaving Melbourne for Southampton. That was his payback.

My father on board RHMS Ellinis, 1967

The Greengrocer to the Stars

A New Role

My parents spent every last penny they had on return tickets to England.

My father took three jobs. One in the market and another cleaning in a local school before going on to the Adelphi Theatre where he worked once again as a stagehand. This meant that he rose at 4 a.m. and did not get to bed until midnight.

How he coped with that workload is beyond me, and the truth is I don’t think he did. Certainly he drank too much for his own good. Yet it was at this time that I realised he had found another way of earning money as the self-proclaimed Greengrocer to the Stars.

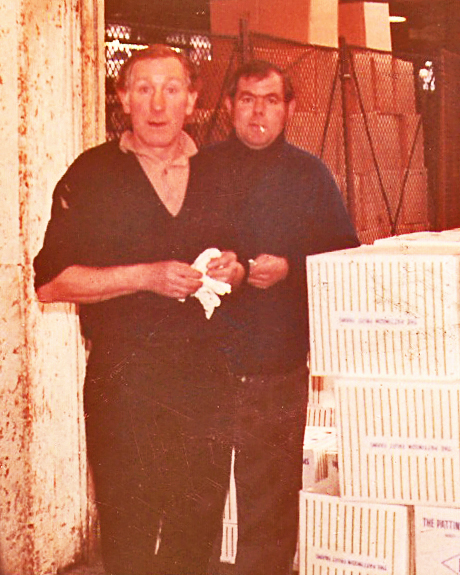

The Greengrocer to the Stars and the stage manager of Showboat. Covent Garden circa 1972

The Adelphi Theatre is located on the Strand. However the dock doors, whereby scenery can enter and leave the theatre, opens onto Maiden Lane at the rear of the building.

And so it came to pass that instead of moving scenery, my father would take orders for fruit and vegetables from the cast, stage management and crew. He would then announce he had to leave, and so he would ask another stagehand to oblige.

“Cover my cues.” he would say, or rather instruct.

I know this because I eventually became his go-to man to cover his job as well as mine.

He would then disappear into the night before returning with a barrow stacked to the heavens.

A stagehand would open the dock doors. My father would enter the theatre at the back of the stage. Then he would unload and arrange everything in time for interval when the large cast exited the stage. They collected their goods, and at some later time they settled their accounts without fuss.

At Christmas, company members ordered trees. Dad delivered these on time – he was keen on punctuality – and offered a splendid discount. He was generous with his wares. Actors and dancers, musicians and stage managers, liked him, and they invited him to their homes.

He had previous form for this. As a child I recall attending Christmas parties at University College Hospital, where I was born. He supplied trees and treats for the children. Naturally the nursing staff thought he was wonderful. My mother would raise an eyebrow, and she would look at me with a look that said, Hush.

So where precisely did he acquire this produce?

Corruption Redux

More Family Business

Enter my father’s distant cousin. I will refer to him as Cousin C.

Cousin C worked as a night-man for a firm in Covent Garden Market. His job was to unload trucks that arrived during the night. And so it was that Cousin C became the chief supplier for The Greengrocer to the Stars.

Their business thrived. Household names purchased produce at knockdown prices. Sick children and nurses smiled. Everyone was happy.

Then one night, shortly before Christmas, when snow lay thick and even on the ground, my father ran into trouble. A young and bushy-tailed constable called a halt to festive proceedings on Maiden Lane.

The conversation proceeded along familiar lines:

“Good evening, sir. Where do you think you’re going?”

“Evening, officer. Just running a few errands.”

“I see. And where did you get all of this stuff?” Plod asks, inspecting a laden barrow.

“Nothing to worry about, guv. My cousin gave me the gear. Fancy a few oranges? Lovely they are. Fresh in from Morocco.”

“Are you trying to bribe me, sir?”

“Wouldn’t dream of it. How about some figs? Or maybe a few pineapples? How about a tree. Got a six-footer you can have.”

“I tell you what,” says Plod. “Maybe we should have a word with your cousin. Now where is he?”

“Think he’s in the Coach and Horses. Or maybe it was the King’s Head. He was a bit vague about it. Then again maybe it was the White Hart. Then there’s the Snake Pit of course.”

“I’ve got plenty of time,” says Plod. “Let’s go look. Shall we? And bring the barrow.”

A time-consuming and arduous trek through Covent Garden finally bears fruit.

On entering the Nell of the Old Drury, Plod, who firmly believes he is about to make a good collar, approaches Cousin C.

Cousin C stands alongside a bar. He is enjoying a pint of warm beer, a whisky chaser, and a quiet smoke of a cigar, when he spies trouble.

“Fuck it,” he mutters to himself.

“Good evening, sir,” Plod says. “Mr C, isn’t it?”

“What of it?” Cousin C replies, ignoring plaintive looks from The Greengrocer to the Stars.

“I have a question for you. Do you know this man?”

Cousin C takes a cursory glance at his confederate. Then he shakes his head and says, “Nah. Never seen him before in my life.”

Plod arrested my father, and they made their way to Bow Street Police Station. It was a short distance, but it was to cause my father to break into a Yuletide sweat.

However, Cousin C arrived in time to save the day.

“I was just having a laugh,” says Cousin C. “I swear Mack bought the gear with his own money.”

Whereupon Cousin C pulls out a wedge of banknotes.

“Here,” he says. “Count it.”

Cousin C goes so far as to say that my father intended to distribute the produce to poor actors.

My father chimes in and says, “Most of them haven’t got two halfpennies to rub together.”

“That’s right,” says Cousin C. “So you see, officer. Mack was just performing an act of charity. And after all it is Christmas. Fancy a tree?”

Bent Coppers

The Pornography Scam AKA Bonkbusters

Police released my father without charge. But given what I know about that police station, at that particular time, it may have taken more than an explanation of just having a laugh, or an act of charity, to get him out of jail.

Police corruption in Central London was widespread, and several West End police stations hired out pornographic films.

Theatre technicians sometimes showed these 8mm productions backstage. These performances would either take place during the show or on matinee days between afternoon and evening performances.

The supply of these films formed part of a racket run by corrupt cops belonging to the Obscene Publications Squad.

The squad was based in Holborn. These officers raided Soho porn shops, and they confiscated material. Then they either sold it back to the owners or, as in the case I refer to, kept some back for hire. Bow Street was one several police stations that hired out these films for a fee.

Fencing and Theft

At the same time, the Adelphi Theatre had become an Aladdin’s Cave. A network of stagehands were fencing stolen goods, mostly high-end audio and optical equipment. The business was brisk and lucrative.

The theatre itself was also prone to theft.

During a lull between productions – the term is dark – I counted every stage weight in the theatre. When I compared the tally with the records I realised that more than a thousand lead weights were missing.

The culprit was a stagehand who during his tenure had removed these weights, sometimes taking two at a time away with him at the end of his shift. That was approximately 25 kilos of of lead per load. Scale that up and one arrives at a figure of approximately 12.5 metric tonnes of lead, that had taken a walk out of the Adelphi stage door.

Nine Elms

The Lansing Bagnall Scam

In November 1974, Covent Garden Market upped sticks and moved to Nine Elms in Vauxhall, and my father went with it.

Meanwhile, firms invested in Lansing Bagnall fork-lift trucks. Inevitably there were those who saw an opportunity to enrich themselves. As a result, porters soon found themselves short of equipment.

The solution was fairly straightforward. A porter from one firm would steal a fork-lift from another firm. He would drive it back to his firm where the truck was re-sprayed in a different colour.

Naturally this caused problems.

When a porter accosted my father. The conversation went something like this:

“Oi, Mack. I reckon you nicked our fork-lift.”

“Nah. Just your imagination, Charlie.”

“Well let’s see about that. Shall we?”

Charlie takes a coin from his pocket and scrapes paint from the red fork-lift.

“There you go,” he says “That’s blue. That’s our colour.”

My father reaches into his own pocket and he too fetches out a coin. Then he proceeds to scrape away the blue paint.

“There you go,” he says “Yellow paint. Now fuck off.”

My father (left) New Covent Garden Market, Nine Elms, circa 1975

The market authorities at Nine Elms attempted to counter theft by installing CCTV cameras. But they were fighting a lost battle; porters stole the cameras.

Certainly my father’s days of ducking and diving had yet to be curtailed. If anything he went into overdrive for several years in order to rescue his familiar parlous finances. Yet he always claimed greed was not a driving factor. He swore that he never took more than a firm could afford. Self justification no doubt, and an attempt to excuse the effects of his contribution to a serious problem. Because theft at Nine Elms forced several firms into bankruptcy.

Dad worked at Nine Elms until his mid-seventies by which time he was very ill with prostate cancer, not that he did anything about it until he was beyond help. His doctor told me that Dad would be dead in three months. He managed another two years.

Dad, Spain, circa 1992

One Last Hurrah

Time for Tea

One afternoon, towards the end of his life, I visited him and my mother. She asked if he would go to the local supermarket and buy some cakes for tea.

I offered to join him and so we walked slowly to the shop. When we arrived, he greeted members of staff like long lost friends.

“You alright, love?” He asked.

“Yeah, Mack. And you?”

“Mustn’t grumble.”

We made our way around the supermarket. I picked up a few cream cakes and a pint of milk, and I placed them in a basket. Meanwhile he continued to greet and crack jokes with the staff. Then we went to the checkout where he paid for the goods.

We chatted as we made our way back. Nothing of consequence. The weather. Football. The Government. The usual subjects. Then, when we got back, I placed everything on the kitchen table, and so did he.

From inside his coat he produced three packs of smoked salmon and several rounds of cheese. This magician’s act also included some excellent dried meats.

I was speechless. I had no inkling that he had taken any of it.

My mother simply smiled and said, “You know what he’s like. He’ll never change.”

Headstone, Hatfield, Hertfordshire