Two Road Trips

Welcome to New York

In late 1973, I arrived at JFK airport, New York. I was travelling with a friend, Kev Scudder.

I had $600, a degree in an Aeronautical Engineering, and a yearning to see America. I was also young and stupid, with long hair, a backpack, and wearing an ex US Army combat jacket – hey, it was the Seventies – proudly purchased from Lawrence Corner.

The plane, a Freddie Laker special, was packed. However, only two passengers were selected for an immigration interview. I blamed Kev.

The interview was conducted by a former bit part player from any American war film one cares to mention. He was thick-necked, a bull of a man with cropped hair. In fact the crop was more a fuzz of razor wire.

He looked at me and sneered. That’s when I knew things were going to be tricky.

Now, we did have a return tickets, Freddie promised to fly us back … a year from that day. We also had visas, properly stamped in our passports, the famous blue ones that opened any foreign door known to mankind.

Unfortunately Razorhead hadn’t got the memo. All he could see were two Limey hippies who were clearly going to outstay their welcome.

“You’ve got two weeks to get out of my country,” he growled. And it was his country. No doubt he had served his country. Marines I thought.

He was no mood to negotiate. Even I could read the room.

We got out of New York, leaving Port Authority where a teen topped by a pith helmet asked me where I was going.

“Philadelphia,” I replied, winningly.

He nodded and then stepped to the ticket kiosk.

“Ten tickets to Philly.”

Having boarded the Greyhound, the gang took seats behind us while I gently broke the news to Kev.

However I had a plan, a cunning one.

“When we get there,” I whispered to Kev, “we grab our packs and leg it.”

In those days, I was fast on my feet, and Kev was no slouch. There again, fear of armed robbery engenders one with a sense urgency.

We made sure to get off the bus in allegro time. The gang gave chase. Yet they were no match for the supercharged Limeys. We ran down a set of steps to a subway. Then we hurdled the ticket barriers and jumped on a waiting train. The doors closed. Then I gave a nice two-fingered English goodbye to our erstwhile travel companions as the train pulled out the station.

We had no idea where we were heading until we reached the end of line, soon discovering we were outside the city. Then we began hitching lifts, thus beginning the first of two road trips.

We never waited long. Hitching a ride on an Interstate was illegal, and drivers picked us up before the cops did. These kind folk often invited to us their homes. Such generosity caught us by surprise. It was all very un-English.

We stayed in Delaware and then Maryland, where we learned about ride-boards. These notices were to be found in colleges whereby drivers and students could link up and arrange trips. We found one in Georgetown, DC.

DC to Denver

In DC we met with a bunch of guys who offered us a ride in exchange for splitting gas.

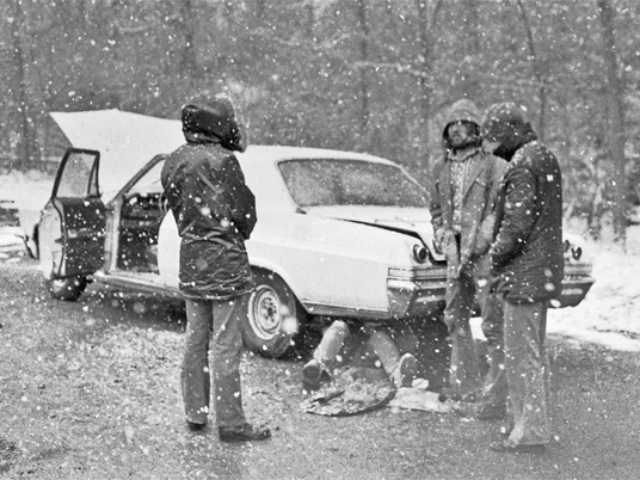

Left to right, Fuzzy, Kev, and FP, rest-stop Interstate 70, November 1973

left to right, John, Fuzzy beneath the car, FP, and Kev

Fuzzy, an army vet, owned a ’65 Ford Fairlane. His friend, FP was taking his first trip outside of West Virginia. The third guy, John, claimed his mother was a US diplomat in Saigon, and that he used her diplomatic bag to smuggle opium out of Vietnam. True or false? Who knows, but I met a lot of crazy people on the road, and I wouldn’t put past someone to do that. A few years later I was reminded of it when seeing Dog Soldiers (titled Who’ll Stop the Rain in the US), that has a similar plot line.

Drugs

When I first climbed into the back of the car, Fuzzy reached under the steering wheel for a small tin. He open it, pulled out a large black gobber-stopper-sized pill and swallowed it.

“Hmm,” he said, smacking his lips. “Black beauty. Let’s hit the road.”

Apart from stopping at gas stations, fixing a breakdown soon after leaving DC, and one rest stop on I-70, Fuzzy drove non-stop covering 1600 miles in 33 hours.

At one point, in the middle of the night, near Colombus, Ohio, I was roused from sleep by the sounds of a harmonica. Everyone else was sound asleep. Thankfully not Fuzzy. He was steering the car with his elbows while simultaneously getting a tune from his harmonica. I didn’t care to disturb him, and so fell back asleep.

We got out on the outskirts of Denver, stayed in a cheap hotel blessed with running water and cockroaches.

From Denver we hitched on I-25 through Colorado and New Mexico before finding our way to Arizona, spending time near Flagstaff and the Grand Canyon.

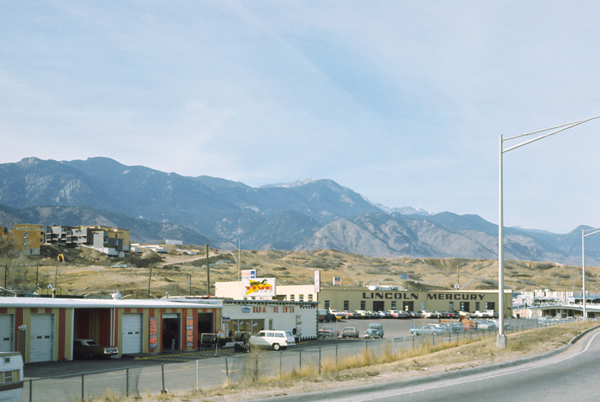

Backpacks, I-25, Colorado

I-25 Colorado, 1973

In New Mexico we were forced to wait an hour on the I-25 It was night and the temperature plummeted. We wanted to get to Las Vegas, a small town in New Mexcio.

A guy picked us up. He was going to Las Vegas, Nevada. I sat up front. Kev slept in the back. It was an overnight drive. I got talking to the driver. He said he made films.

“What kind?” I asked.

“Adult,” he replied Then he handed me a card. “In case you’re interested in a job.”

After breakfast in a roadside diner we parted company.

We caught several rides before reaching Los Angeles, staying overnight in a Santa Monica hotel, which is when disaster struck. Not that I realised it.

After returning from a restaurant, I collapsed on steps leading to the hotel lobby. It was as if someone had stabbed me in the back. Kev helped me to my bed, and I spent the night in considerable pain.

The following day we left and headed for the highway. I was still in pain and limping. I was twenty-one years old, fit and strong. So I didn’t think much of it. I intend to write more about this in a separate essay, because it has had implications for my life as an artist. In the meantime, the short version is that I was suffering from ankylosing spondylitis, which was not diagnosed until 1989.

Race and Murder

We caught a ride on State Route 1 with a bunch guys who lived in San Francisco. We hit it off straightaway.

Doug, the driver was Canadian, and a photographer. Dick Konig and Lee Hudson were longtime friends from Bowling Green State University. Lee had served two years military service as a medical orderly in the Presidio. When he left, Dick joined him in San Francisco. Dick previously worked as an accountant for Hughes Air West. He said he had been fired after trying to tell Howard Hughes that he, Hughes, was being robbed blind by some HAW employees.

Dick and Lee formed a business partnership, American Enterprises. They had been selling meat in the city, sourced from a ranch in Northern California. Unfortunately the Mafia had other other ideas. After receiving a home visit, the two would be beef merchants immediately retired. Instead they turned to selling art.

The other guy was Steve, a gentle man steeped in Eastern philosophy.

Steve, getting spiritual, Marin County

Doug lived in a former brothel in the Fillmore District. Kev and I stayed with him while Dick and Lee shared an apartment in Ocean Beach. It was an upmarket part of the city whereas Doug’s address proved to be a matter of wide-eyed wonder at a party in a smarter district of the city.

While there, we were within earshot of a shooting. The Zebra murders were racially motivated homicides that left 15 white people dead. That figure is held to be inaccurate by some who claim the killings began much earlier. The serial killers weren’t apprehended until May of the following year.

Ivy Street, 1973, the former brothel was on the right by the trees

Basketball court, Fillmore, 1973

Both Kev and I were running short of money. We need to find work. Dick and the others were instrumental in getting our visas extended by six months. Then it was a simple matter of obtaining a Social Security card.

Then my spinal pain returned and I was worried something was seriously wrong. I wasn’t in a position to afford medical treatment, and I couldn’t bring myself to admit it to the others.

I loved San Francisco. Part of me wanted to stay, but I knew I had to get back to London. So I made a vague excuse about having to return home.

left to right, Doug, Steve and Kev, Santa Cruz, 1974

Guns

In January ’74, I travelled alone, getting a ride with a couple of surfers whose home was in New York. We made our way in deep winter across the Sierra Nevada and into Wyoming. 200 miles of solid ice without snow chains made for an interesting ride.

One had thirty seconds to make it from the car to the inside of a gas station. That’s because it was 40 below zero with a wind chill factor of 20.

Wyoming in winter, 1974

The surfers wanted to know about Britain and also what I thought of the States. I said I loved the country, and the people. But I had one reservation, gun ownership. That was the only time the conversation became heated. Guns were needed to defend people against home invasions and it was a god-given right to bear arms.

It was a lesson not get between Americans and their guns.

After four days, we parted company at Port Authority, New York, which is when I discovered the car’s trunk was filled with rifles and ammunition. At that time in New York, carrying a firearm merited a mandatory 20-years in prison.

Surfers or gun-runners?

Kindness, dope, and race

I bussed south to Virginia, staying in Bryan House, Williamsburg. It was home to my great aunt, Vi, and her husband, Rob. He was a cabinet maker and employed to help reconstruct furniture for Colonial Williamsburg. Bryan House formed part of that restoration, and it was not permitted to have air conditioning, which Vi said made the house very uncomfortable during the summer.

Bryan House, Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, January 1974

Vi was very kind. I had lost a lot of weight. Clothes were hanging off me. She fed me, incessantly for a week.

Their youngest son, Rick, was a talented musician. A multi-instrumentalist who had once toured as a drummer for The Inkspots, although I doubt any of the original members were part of that group, given the number who played under the name.

Rick had another talent. He was a drug dealer, growing a plantation of weed in the Blue Ridge Mountains. He had recently downsized following the murder of his business partner in Nashville. The victim’s body was dumped in the trunk of a car with a warning for Rick. Stay out of Tennessee.

Rick’s bedroom cupboard was stacked with rifles. No doubt for self defence. It was another reminder of the Second Amendment.

Rick and I had a similar taste in music. I met his friends. One was a DJ on an FM station at the William & Mary university. He invited me to sit in with him for a three-hour show. I got to choose all the music.

The phones lit up when I played Steely Dan’s My Old School.

I was smoking with the boys upstairs when I

Donald Fagen and Walter Becker

Heard about the whole affair, I said oh no

William and Mary won’t do

Rick and the DJ took me to a bar just outside Richmond. I mistakenly thought the 1964 Civil Rights Act had put an end to segregation. As we approached the bar, I noted there were two entrances. Rick guided me to the right. When I asked him why, he said, “Whites go right. Blacks go left.”

I was mostly met with nothing but kindness and generosity by Americans from all walks of life. However, the greatest takeaway from my time in the US was a country wracked by race, drugs, guns, and violence; I don’t think that’s changed.

I returned to London and an airport surrounded by armoured cars. Supposedly protecting Heathrow from a terrorist attack.

Shortly afterwards, I began a seemingly endless round of hospital visits, each one as disappointing as the next.

Was I right to leave California? I did wonder if I had made the right choice. Then one very grey day in 1979, I walked into London’s National Gallery and turned my life around.