A few years ago, I searched for my grandfather, Frank Cave, formerly of the 15th Battalion, Australian Imperial Force. Or at least I went looking for his ghost since I knew he was long dead. He was a survivor of the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign, and that fact provided me with a good place to start.

A Name …

and a face

I knew that his full name was Francis Horace Cave, an Australian who had fought in the First World War. I also had one photograph of him in uniform. My mother kept his picture close until she died.

I also knew that his arrival in England, in less than auspicious circumstances, led to her birth in the hours following Armistice Day, November 11, 1918.

Frank Cave, AIF

Fortunately, Australian archives, much of it available on the internet, provided a considerably fuller picture.

Early Years

When Life was a Picnic

Frank Cave, was born in Fitzroy North, a suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, in 1892. He later claimed that his father, John Newman Cave, was a diamond setter. My mother told me that Frank’s mother, Emily Frances (née Pilkington), was a piano teacher.

In 1911, Frank had his first reported scrape with the law. It was an innocuous enough incident, but one which upset some of those on the foreshore of Mornington beach.

It was a hot day in March when young Frank, who claimed to be a member of the Wood Workers Picnic, was ‘enticed to bathe nude‘. That didn’t wash with the local police, and so they arrested him.

Frank subsequently pleaded Guilty, which with hindsight proved to be a rare occurrence, and a judge fined him the grand sum of £1.

War

Frank Cave Enlists in the Australian Imperial Force

In 1914, Great Britain declared war on Germany. There was a call to arms across the Empire, and so Frank Cave travelled from his native state to Queensland in order to enlist in the newly formed Australian Imperial Force (AIF).

Why he went to Queensland is unknown. It is possible enlisting officers in Melbourne rejected him. He was far from tall, 5-8, and the first draft concentrated on selecting bigger men. It is also possible that he was running from the law. He would not have been the only one escaping Australia for the same reason.

But no matter, because on September 23, in Toowoomba, he met with success, and he swore to ‘well and truly serve our Lord Sovereign the King‘.

After leaving Queensland, he found himself back in Victoria, receiving training at Broadmeadows.

Frank Cave (circled). 15th Battalion, E Company. Broadmeadows, December, 1914. 24 of these men would be dead within 12 months.

The officer standing front row, second from right, is Hugh Quinn.

Hugh Quinn

Quinn’s Post in Gallipoli was the bloodiest section of the front line. Quinn died defending it during a Turkish attack.

The Fleet Sails, Destination Unknown

On November 1, 1914, the AIF set sail from King George’s Sound in Western Australia.

When the fleet docked in Columbo, Ceylon, several soldiers either deserted or went on a drunken spree. As a result, when the fleet next stopped in Aden, authorities confined the troops to their ships .

Finally, after much debate as to their final destination, the AIF disembarked in Egypt, which was where the trouble really began.

Egypt

The Curse of the Wozzer

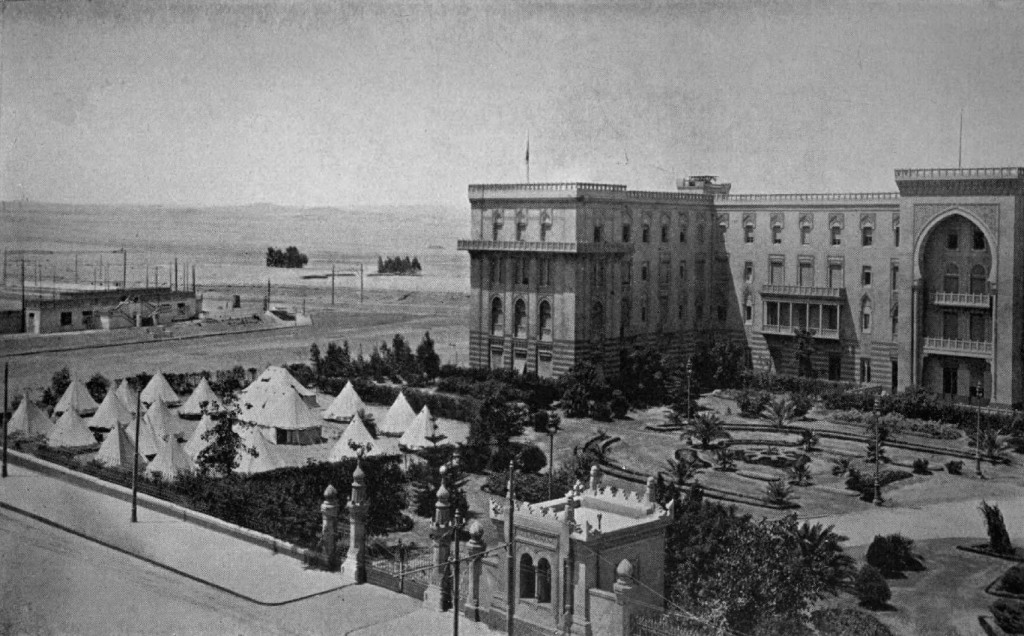

On arrival in Egypt, the 15th Battalion, part of the 4th Infantry Brigade, set up camp on a former aerodrome in Heliopolis.

4th Australian Infantry Brigade tent and horse lines at Heliopolis

The town was only a few years old and stood on the edge of the Sahara, some eight miles from Cairo’s centre. But it was the city, rather than the more sedate environs of the camp, which acted as a magnet for Australian soldiers who quickly made themselves extremely unpopular with the locals.

In return, the Cairenes exacted their retribution. Cooks and waiters applied a well-placed hand-wipe to plates of food. Drinking establishments sold doctored alcohol. Even more insidious were those who inhabited the streets surrounding the Ezbekiah district, and in particular the Harat el Wasser, known to the Australians as the Wozzer.

The 15th Battalion diary for March records my grandfather’s presence thus:

No: 727 Pte Cave, F.H. No: 3 Co: Admitted to Venereal Hospital 2/3/15

Thus began the first of frequent stays in an army hospital bed.

Consequently, when the 4th Infantry Brigade set sail for the Dardanelles, Frank Cave was otherwise detained.

Isolation tents for infectious diseases. Palace Hotel, Heliopolis, 1915

Before the war, the Palace Hotel was regarded as the finest in Africa. Frank Cave spent time there in March 1915. The tents, which were placed in the hotel’s gardens, also housed those with measles.

Aftermath of a lethal riot in the Wozzer on Good Friday, April 2, 1915, when 4000 soldiers attacked pimps and prostitutes, setting alight the brothels. Source: Museum Victoria (left), AWM (right)

Gallipoli

A Casualty of War

On July 3, 1915, Frank Cave arrived in Gallipoli.

The battle against Turkish soldiers had reached a deadlock. Australian forces, together with New Zealand and Indian troops, were unable to make headway.

Meanwhile, Turkish forces subjected them to constant sniper and artillery fire. Furthermore, due to the squalid conditions they were forced to endure, the Imperial troops also suffered terribly from disease and sickness.

In August, Allied commanders hatched a plan to break out from the beach.

On the night of August 6, men of the 15th Battalion attempted to take Hill 971 (its height in metres). However the Australians failed to achieve their objective.

That night, a Turkish soldier shot Frank Cave in the left thigh. Stretcher bearers took him to a clearing station on the beach.

Koja Chemen Tepe

Hill 971. The Turks called it Koja Chemen Tepe, which translates approximately to ‘The Great Grass Mountain’.

Between August 6 and 9, the 15th Battalion, which consisted of 600 men, suffered nearly 400 casualties.

Sick in Egypt

Imprisoned in France

Frank Cave returned to Egypt. He was hospitalised in Alexandria and then in Cairo.

In October 1915, he rejoined his battalion, but soon afterwards he went absent without leave (AWL).

As a result, the battalion disciplined him, and when the curse of the Wozzer returned he was again hospitalised in Abbassia, Cairo.

In June 1916, he found himself in France, first Marseille and then a hospital in Etaples. He escaped, but eventually military police arrested and imprisoned him; then he escaped again.

In January 1917, after arrest by British Red Caps in Paris, he faced a Court Martial.

If he had been British, the authorities would most likely have shot him for desertion. But the Australians, despite intense pressure from the British, refused to execute their own men.

Consequently a Court Martial gave Frank Cave the equivalent of a slap on the wrist, for which I am eternally grateful, and he received 6 months hard labour.

War may have been a profitable exercise for some, but at that stage Frank had forfeited a total of 241 days pay. However all was not lost, because In February military authorities suspended the sentence of hard labour.

England

Court Martial and Marriage

Once released, he joined the 47th Battalion.

Nevertheless Frank avoided front line service because he needed medical care. As a result, he entered No. 1 Australian Dermatological Hospital in Bulford, Dorset.

No. 1 ADH Bulford

In August 1917, Frank Cave left Bulford. But in late October he received orders to join the Overseas Training Brigade in Longbridge.

Unsurprisingly, Frank failed to report for duty, and he remained AWL until military police apprehended him in London on January 14, 1918.

Once again he escaped. Then police re-arrested him on February 18.

He now faced a second Court Martial. He pleaded Not Guilty to one charge, that of failing to report for duty in October when ordered to do so. But he pleaded Guilty to the second charge of being an illegal absentee.

In the event, a court found him guilty of both charges and sentenced him to 70 days in Lewes Detention Barracks, near Brighton.

He was freed in May and sent for training. Then he returned to France, although not for long.

On July 11, 1918, Frank Cave married Gladys Haywood in St. Philip’s Church, Battersea, London.

On July 26, he returned to France. This time he joined the 49th Battalion, and that is where he remained until October when he was repatriated to Australia.

He was aboard a ship when the war ended. That same day, my grandmother, while celebrating the Armistice in Trafalgar Square, went into labour. A police officer helped her away, and he took her to St. Thomas’ Hospital where she gave birth to my mother in the early hours of November 12. Therefore I think it is safe to say that by the time of Frank Cave’s arrest in February, not only did he know my grandmother but she was also pregnant by him.

Back to Australia

A Broken Promise

On January 31, 1919, the Australian Army discharged Frank Cave. Soon afterwards, my mother and grandmother set sail for Australia.

Once in Melbourne, they lived with Frank and his mother. However my grandmother became homesick and so he encouraged her to return to England with my mother.

On attempting to board the Themistocles, my grandmother discovered her passport was missing. She had her suspicions, and she believed Frank had stolen it.

Nonetheless she and my mother were permitted to continue their voyage, and they arrived in England on April 29, 1920.

The Themistocles of the Aberdeen shipping line.

Frank Cave promised to join them later. He never did, instead he chose another course.

A Suspected Person

Bigamy

Australian records show that in 1920, Frank Cave married Susan Turner. I believe that the marriage took place after my grandmother left the country.

My mother claimed that she had a half-sister, in other words Frank Cave’s daughter. It is certainly true that someone claimed to be his wife when contacting military authorities.

Pickpocket

In August 1922, following a visit to a Melbourne restaurant, police arrested Frank and his friend, Arthur Gilbert, charging them with assault and wilful damage of property.

The pair were acting as pickpockets, and when Gilbert attempted to dip a diner, a fight ensued and Frank Cave hit the man in the eye.

A witness had this to say:

Cave knocked over a screen and a dinner waggon loaded with crockery, took plates from the hands of a waiter and threw them about, broke a chair, and kicked over a table … When Cave had finished you could not tell whether it was a cafe or a pig stye.

A judge fined Frank Cave £5 on each charge and £10 damages. Frank also had to pay Gilbert’s bail because his confederate failed to show up at the court.

Frank Cave, South Australia Police Files, 1923

In April 1923, following a tip-off from counterparts in Melbourne, Adelaide police arrested Frank Cave and John Christie.

The pair were intent on pick-pocketing, this time at the races in Adelaide.

Police charged them with ‘having insufficient means of support and being suspected persons‘.

Frank Cave had just 3/6 in his pockets. Nonetheless he pleaded Not Guilty.

In court, he gave his occupation as a carpenter, and he also claimed that he met Christie only days before his arrest.

Frank told the court that he arrived in Adelaide in order to borrow money from friends. Police proved this was a lie. He also claimed to have been in constant employment since 1912, not that he provided details of his military career.

A judge found him Guilty and he offered Frank a choice. Either Frank could serve 6 weeks’ imprisonment, or he could board the next train leaving Adelaide.

In November of that year, police in Melbourne went on strike. However that did not prevent one of them from arresting Frank.

The charge, which followed an incident involving stolen jewellery, was also ‘having insufficient means of support‘.

The outcome is unknown, but in May 1924 police arrested him on the same offence. Nevertheless Frank walked away scot-free.

An Interstate Reputation

At this juncture, Frank Cave had earned a reputation as an interstate pickpocket.

In November 1924, detectives arrested him, along with three others, at Caulfield Race Course in Melbourne.

One detective told a court that the quartet were ‘gamer than Ned Kelly’s gang‘.

A jury found Frank Cave Guilty and the judge sentenced him to 6 months’ imprisonment.

Frank left prison in April 1925. But in October, following a football match at Melbourne Cricket Ground, police again arrested him for pick-pocketing. This time a judge sentenced him to 12 months’ imprisonment.

Aliases

Frank Cave, like many criminals, used a number of aliases, including Frank Wilson, Francis Gilbert, Francis Burns and John Christie. He travelled extensively, and committed crimes in Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland.

Passenger lists for the era when he was active show the presence of F.H. Cave taking a number of voyages overseas.

My mother claimed that at some point after WW1 her father served time in Brixton Prison. If true, when did he visit London?

There is one case that fits the bill.

In 1930, London police arrested an Australian confidence trickster named Frank Wilson. A jury found him Guilty of fraud, and a judge sentenced him to 3 months’ imprisonment. It is also true that Frank Cave committed similar crimes.

In September 1939, shortly after the outbreak of WW2, a woman claiming to be Frank Cave’s wife wrote to the military authorities from an address in Glenelg, South Australia. She asked for a copy of his army discharge papers. She claimed he was unable to write for himself, and she said it was a matter of urgency. This was not the first request for these documents. Frank had made a similar request following his arrest at Brisbane racecourse in 1927.

But why then?

Maybe, yet again, police had arrested him. However in April 1941 they most certainly did.

There Will Always be an England

Hard Labour

Frank Cave was living in Brighton, a seaside town close to Adelaide. when police arrested him and two accomplices.

The three faced a charge of defrauding members of the public by exploiting feelings of patriotism.

Frank and his mates had arranged for someone to print stickers, approximately the size of a postcard, bearing pictures of a Union Jack and the head of Winston Churchill.

The stickers carried a slogan: There will always be an England.

The printing cost of each was 2¼ pence.

At first, the three said they wanted 50,000 printed, later reduced to 30,000. Finally, they settled for a paltry 500.

They travelled the state in a borrowed car, and they had prepared a sales pitch.

“Put your hands in your pockets, ladies and gentleman. Two bob each. Show your appreciation for the boys over there. Cos every penny is going to the Red Cross … And what was the other one? Oh yeah. The Fighting Forces Comforts Fund.”

When finally apprehended by police, the gang produced two receipts, both for little more than £1, paid, as promised, to the Red Cross and Fighting Forces Comforts Funds.

Police were unable to prove how many certificates the gang had sold. But when it came to court, the prosecution called 20 witnesses Naturally the three pleaded Not Guilty, and naturally the jury decided otherwise.

A judge sentenced Frank to 9 months’ imprisonment in Yatala Labour Prison.

He left Yatala in December 1941, and he eventually settled in Sydney, New South Wales where he saw out his days.

He may have re-offended. I cannot believe he remained on the straight and narrow. But he never spent another day in prison.

My Mother’s Search

So close and yet …

In October 1965, my parents emigrated to Australia. In part it stemmed from their wish to make a better life for their children. However there was also my mother’s determination to find her father.

We lived in South Australia, and eventually, with the help of the Salvation Army, my mother discovered that her father was living in a hostel in Sydney. Despite her pleas to see him, he refused, saying if she was looking for money she was wasting her time because he had none.

Instead, she met his brother, Otway Hamlet Cave, who lived in Melbourne.

Left to right, Otway Cave, my mother, Otway’s wife, my father, my brother Jamie. (front) my sister Lorraine and my brother Shaun

Otway apologised for his brother’s behaviour, describing Frank as ‘the black sheep of the family‘.

We left Australia the following day on board the RHMS Ellinis bound for England, stopping in Sydney.

The ship remained moored alongside the Sydney Harbour Bridge for a day and a night. We went ashore, and we even stood on that famous bridge, but what we failed to do was cross it.

RHMS Ellinis in Sydney Harbour, late 1967

Some 50 years later, I discovered that Frank Cave was living a few hundred yards from the far side of the bridge.

End of the Line

Field of Mars

Frank Cave died in Concord Hospital, Sydney on July 8, 1968. His grave is in the Church of England Cemetery, Field of Mars (grave no. 3155).

Even to the last he avoided telling the truth. Despite him knowing otherwise, his death certificate states he was a widower, that his wife Gladys died at the age of 28 — in fact my grandmother outlived him — and that he had no children. I have archived photographs taken during our voyage from Adelaide to Çuracao